Minerals, Fossils, and Human Evolution

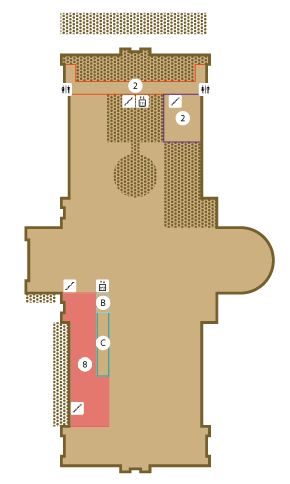

The exhibition starts off with a journey through the history of Earth, an over 4,500 million-year condensed tour through the fossils of every geological era. Visitors learn about the different types of fossils, the process of fossilization, and the historical aspects of paleontological research. Highlights of the exhibitions are the skeletons of the dinosaurs and the big mammals.

The skeleton of the Diplodocus carnegii is a replica of the skeleton known as Dippy, housed at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Pittsburgh, USA). It was donated by Andrew Carnegie to the king Alfonso XIII and it arrived at the museum in 1913. As with the megatherium, the original mounting is still preserved.

The Gomphotherium angustidens is one of the most complete dinosaur skeletons in Europe. It is as large as an Indian elephant today, reaching up to 2 metres in height.

The Megatherium americanum arrived at the Royal Bureau of Natural History over 200 years ago from Luján (Argentina). Besides being the species holotype, this was the first fossil skeleton mounted in its correct anatomical position, and was studied by G. Cuvier, the father of Paleontology as a scientific discipline.

The section about human evolution reveals the most recent research and discoveries that have changed our understanding of the origins of humanity. It features replicas of the most recent and important human paleontological remains worldwide such as footprints, craniums, bones and even complete skeletons.

Lucy is the most famous hominid of the species Australopithecus afarensis around the world. She is 3,2 million years old and was discovered in Ethiopia. The Museum exhibits a reproduction of this skeleton, which owes its name to the Beatles’ popular song.

The exhibition ends with a sample of the Museum Minerals collection, arranged according to the international classification; visitors here can learn some facts about the use of the minerals, and their industrial or economic importance. Some specimens have been here since the opening of the Museum: metals, precious stones, and high-quality specimens of great beauty which, by the 19th century, were one of the best collections in Europe.

Known as the Inca’s mirror, this astonishing obsidian specimen, polished on both sides, was donated to the museum in 1925.

Scientists today claim that these types of mirrors were used by ancient Mesoamerican cultures to communicate with the spiritual world – more specifically, with the Aztec god Tezcatlicopa.

The crystalized sulfur from Conil de la Frontera (Cádiz) is one of the oldest items in the museum; its perfection and beauty and the size of its crystals remain unchallenged in the world. It arrived at the Royal Bureau in 1792 at the request of the Count of Floridablanca.

The pyromorphite from the mines of El Horcajo (Ciudad Real) has fine acicular crystals which, after the closing of the mines in 1911, are rarely found anywhere else.

The meteorite collection includes 240 pieces from160 individual meteorites. It features whole pieces, fragments and polished sections from all over the world, as well as a superb selection of the meteorites that have fallen in Spain since 1773 to date.

The Allende meteorite is a specimen of immense scientific value, which has given us key information about the conditions that made possible the formation of the solar system. Results of the analysis of its composition have shown the existence of carbon, as well as organic aminoacidic components not known to exist on earth.

You can find the books of the exhibition in the Museum Shop (Megaterio).

|

The books of the exhibition are available at the Museum Shop (Megaterio) |

|

1º planta y 2º planta